Bubble boy disease was termed when David Vetter was born with a disease that robbed him of an immune system rendering the boy to spend his entire life in a sterilized plastic bubble. Bubble boy disease, also called as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), is a rare inherited congenital disorder that is sometimes fatal; characterized by little or no immune response. Due to a dysfunctional immune system, SCID patients are susceptible to viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, sentencing them to a life-long isolation.

Several forms of SCID include:

a problematic gene in the X chromosome (x-linked affecting only males)

a deficiency of the enzyme adenosine deaminase (ADA).

A mutation in the interleukin-2 receptor gamma (IL2RG) gene results to X-linked SCID. This gene produces several IL receptors which play a key role in the proper development of T cells. T cells are important part of the immune system as they hunt and destroy cells that are infected or have become cancerous. If IL2G is defective, invading agents remained unchecked as well as the activation and regulation of other cells of the immune system is compromised.

In the case linked with a deficiency of the enzyme ADA, adenosine and 2'-deoxyadenosine (2-Ado) substrates accumulate in cells which prevents DNA synthesis - especially to immature lymphoid cells. The clinical manifestation of a SCID patient due to ADA deficiency involves low T and B cell counts leading to a high risk of severe infections and lower survival rate. Other manifestations are associated with neurological abnormalities, but for patients with late-onset ADA deficiency, they show an abnormally low level of lymphocytes in the blood (lymphocytopenia).

T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and B cells are lymphocytes that are of great importance in one's immune system. T cells and B cells are responsible for adaptive immune response while NK cells are responsible for innate immune response; that is why if someone's immune system is compromised, they will be highly susceptible to microbial attacks, leading to life-threatening infections.

In a study published on New England Journal of Medicine, an experimental gene therapy showed promising results as it restored functioning immune systems to seven young children with X-linked SCID.

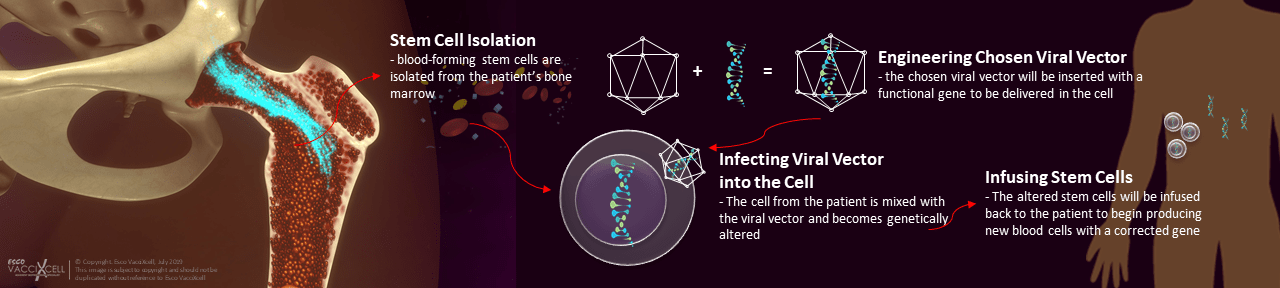

The researchers altered a relative of human-immunodeficiency virus (HIV) to produce proper components of a healthy immune system. The engineered lentiviral vector is inserted with a normal copy of the IL2RG gene to be delivered in the isolated blood-forming stem cells of the patient.

Prior to therapy (infusion), eight infants aged 2 to 14 months with newly diagnosed SCID-X1 underwent low dose chemotherapy to create space for the growth of new bone marrow cells. Within three to four months, seven out of eight participants in the study developed functional immune cells such as T cells, B cells, and NK cells. The initially low T cell count of participant eight increased after a second infusion of the therapy.

Fig.1 A graphical representation of gene therapy workflow

Many studies have been conducted for treating SCID with gene therapy. Viral vectors are commonly utilized due to their ability to penetrate the cell and modify its nuclear genome. The encouraging results demonstrate that this gene therapy approach is safer and more effective.

Earliest trials have reported that although participants partially improved immune responses, they later developed leukemia. Researchers explained that the viral vector used in that gene therapy activates or stimulates genes that control cell growth; however, for this type of gene therapy, the viral vector used was designed to avoid this outcome.

Continuous monitoring is being done for the participants of the study to evaluate the immune capabilities developed as well as potential long-term effects of the therapy. With promising results of this treatment, the future can hope to say, "bubble boy disease no more."

References:

E Mamcarz et al. Lentiviral gene therapy with low dose busulfan for infants with X-SCID. The New England Journal of Medicine, April 17, 2019; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815408

Fischer A. (2000). Severe combined immunodeficiencies (SCID). Clinical and experimental immunology, 122(2), 143-149. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01359.x

NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. (2019, April 17). Gene therapy restores immunity in infants with rare immunodeficiency disease. ScienceDaily. Retrieved July 14, 2019 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/04/190417171019.htm

Sign up to our newsletter and receive the latest news and updates about our products!